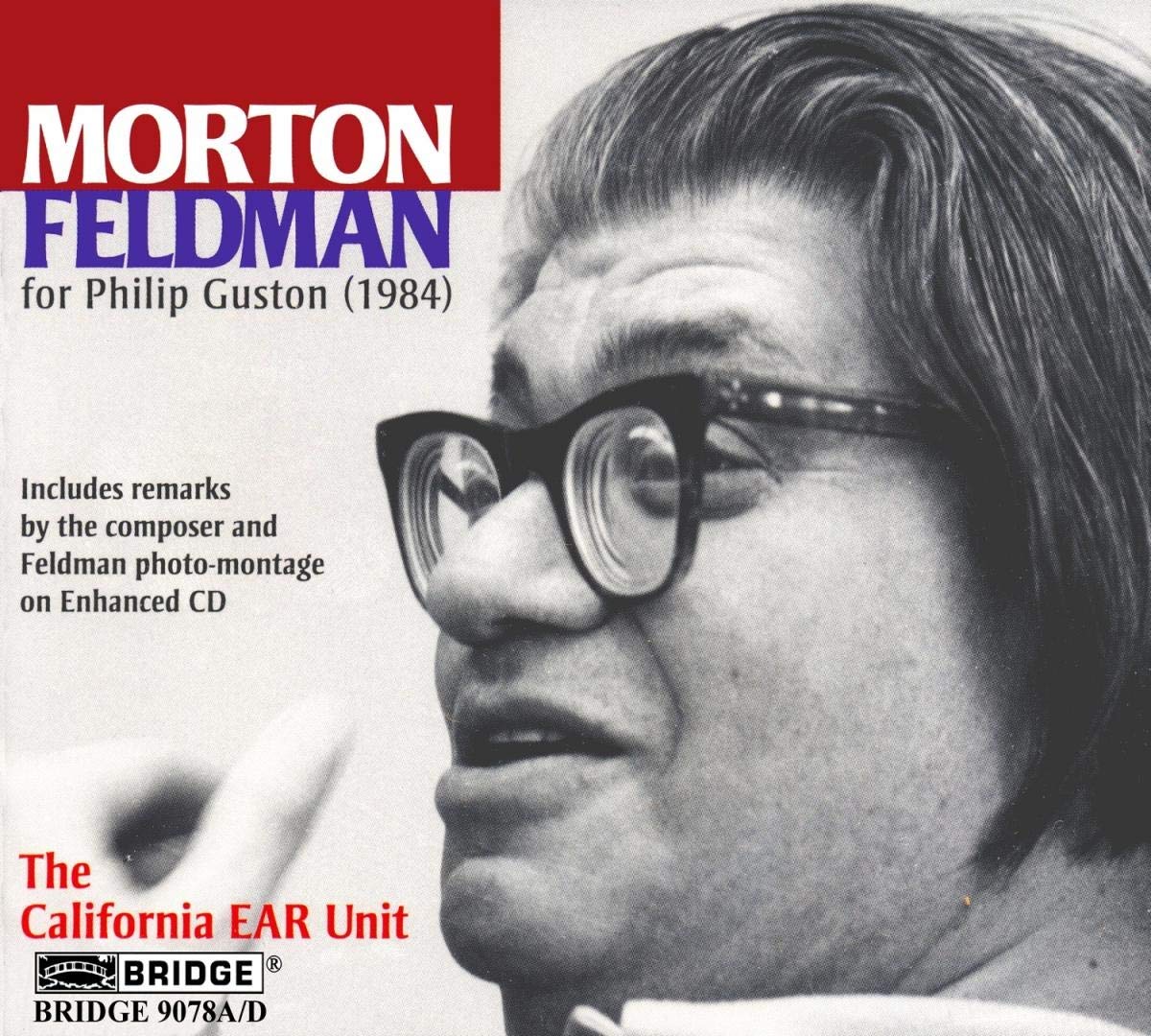

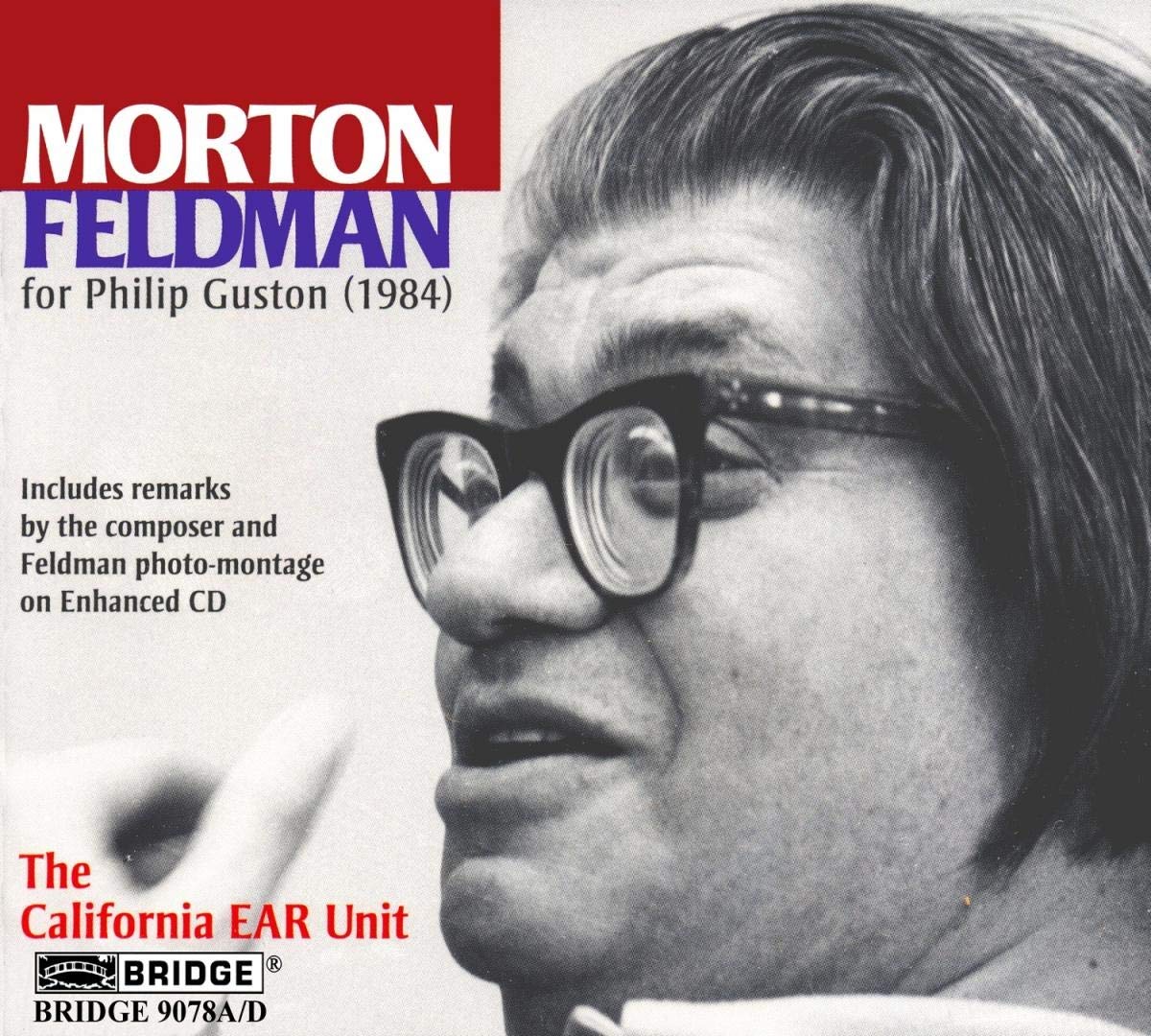

The California EAR Unit - For Philip Guston (Morton Feldman)

1997 | Modern Classical, Chamber Music

I’ve actually come to really love this. It’s not necessarily music you need to devote 100% of your attention to; it’s true there are subtleties in the music itself, but ignoring the technicality of actually playing the piece the overall structure of the composition is pretty simple. There’s very little variation, and the only really noticeable change is in the final 30 minutes. There are other moments of melody sprinkled throughout (most notably the section in "2.3" which foreshadows the ending with a similar melody, only it lacks the emotional impact), but these moments mainly contribute to the image in the listener’s mind rather than the structure of the piece itself. These moments matter less in the grand scheme of things though, as the piece in its entirety should be enjoyed, not just specific sections - if you’re treating the 3+ hours of mostly-atonal turmoil that takes place prior to the final melodic climax as a sort-of “endurance test,” you’re missing the point.

Feldman had an infatuation with the visual arts, painting specifically, and this piece is probably the best example of that (especially due to the name/dedication). This infatuation really bleeds into his compositions - later in his life Feldman was obsessed with the scale of his music, which is a trait that is found in the visual arts, but not a trait commonly found in music. This is why he sought after pushing the limits of what the performers/listeners could handle in terms of length. His longer compositions are akin to paintings in this sense, as it’s music you need to live with to notice the nuances. You won’t notice fine details of the painting in your living room right after you hang it up, you have to live with it to notice the subtleties. It’s the same way with these pieces, including For Philip Guston - after sitting on the composition for a while and revisiting certain parts, the subtleties pop out and the bigger picture begins to form in your mind.

In more literal terms, the atonality of the piece might make it seem like random blobs of color thrown at a canvas, but the more you listen/the more you look at the colors, patterns and shapes that you never noticed before come to fruition. The music is very meditative and minimal, but it's supposed to be. It's stagnate. There isn't supposed to be any movement - if you feel like nothing is happening, it's because nothing was ever supposed to be happening in the first place.

This piece, more than others, has a clearer "idea" due to the last 30 minutes. Feldman was very strict with his atonality, and he rarely gave the listener relief with melody for more than a couple of measures. In the final portion he completely betrays his entire ideology as a composer, and the piece "bursts" into melody (bursts isn't necessarily the right word, because it is Feldman, so this transition is very slight, but due to the relentless tension of the 3+ hours before the moment is extremely emotionally impactful). It's genuinely one of the most beautiful sections in any piece of music, ever, and yet one of the most soul-crushingly sad moments at the same time.

It's unfortunate that many people listen to this as their first avant-classical type piece as it's a really daunting and strange listen if you don't know what to expect. As a result, the music is really misunderstood by the people who got into it in the wrong way. The reception of this piece is completely understandable with this in mind, because it is inherently polarizing music, but I just wish listeners would be more open-minded. Feldman's style as a whole might not be easily digestible at first, but once it's understood it becomes really fascinating music.